Some folks defy categorisation. I sat down one afternoon to speak with a welder, a poet, an environmentalist and a carpenter; as well as a soldier, an actor, and a gardener. Wim (Vim) Bevers is all of these and more, and an active pillar of the Sefton, Balcairn and Amberley communities.

Zeelander

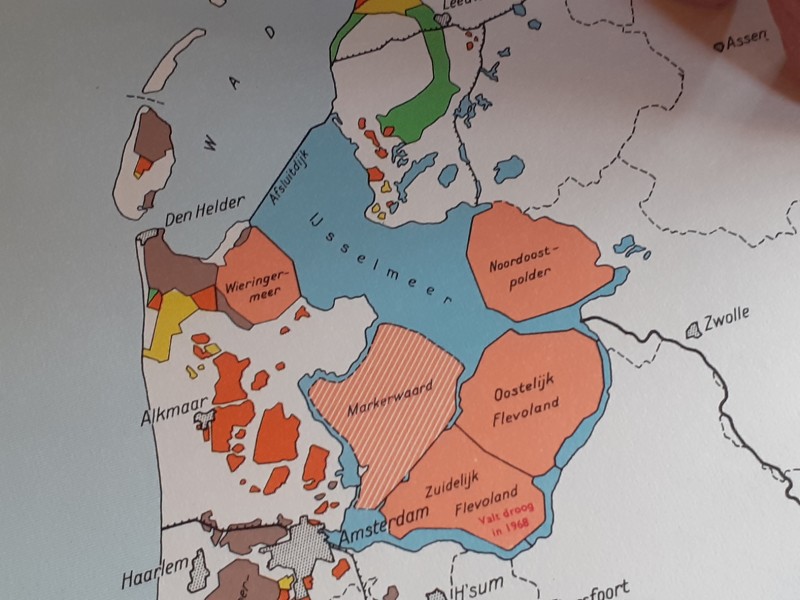

Born into war-torn Holland in 1950, Wim and others of his generation had to grow up quickly and learn a trade to help rebuild their country as it emerged from the rubble. Public work on dams, dikes and land reclamation was underway in the Netherlands on a scale never seen before, with The Zuiderzee Works project dubbed part of the Seven Wonders of the Modern World. As a child, Wim saw mighty GMC troop transporters left behind by American forces being repurposed as work trucks by Dutch locals for hauling materials to fix bridges and other bomb-ravaged infrastructure.

‘We heard lots of stories about the war, and how bad it was. We were often told, “If you don’t eat that, during the war you would have eaten it,” so that was still in people’s minds.’

The demand for practical skills saw Wim train to become a sheet metal engineer with Philips Electrical in Eindhoven, while studying middle-management at night classes. So, when his turn came to serve in the army, he was put in technical services and worked beside mechanics along the East-West border in Germany. ‘The Iron Curtain, as it was called then. I was stationed 40kms away from it in a big British camp with a lot of tanks and other stuff about.’