In-Focus: Taxing farming emissions

Azriel Taylor

Azriel Taylor

Share

Farmers are angry at plans to tax agricultural emissions, leaving government with a battle on its hand to win the rural sector over.

Tractors lined the streets of main cities in protest, with concerns over how it will impact their livelihood and the future of farming.

Behind the protests was farming advocacy group Groundswell, however, Voices For Freedom also had a presence.

Groundswell spokesperson, Steven Cranston says there are too many regulations affecting farming that are discouraging young people from entering the industry, and there's too much criticism.

"There's a massive amount of stress on farmers, it's taking a strain on mental health. It's just coming at farmers from all angles at the moment."

"Because everyone's looking at farmers thinking we are bad when farmers actually really care about the environment and take pride in their farms. We do feel really misrepresented."

Although this plan is recent, there has been a previous attempt to do something similar in 2003, when the Labour Government considered a tax on emissions but was withdrawn due to opposition from farming communities.

Clearly this move is causing a lot of backlash, but how did this all start?

Here's the situation:

Climate Change Minister James Shaw says "by 2025 New Zealand will introduce a system that means farmers pay a price for their emissions and are rewarded for taking action to reduce their climate pollution."

In 2019, the government passed the Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act unanimously, which created the goal of reducing biological methane by 10% of the 2017 figures, by 2030.

Shortly after, they formed He Waka Eke Noa, a partnership of agricultural organisations, Māori, and the government, to create a plan on how to reduce emissions from farming.

For three years they worked together to form a plan and submitted it to the government.

Most recommendations were accepted, but some key changes had farmers upset.

According to the President of Canterbury Federated Farmers, David Acland, there were changes in recognising efforts of sequestration, and a difference in the pricing scheme.

Sequestration is the removal of CO2 from the atmosphere, by photosynthesis through plants which store the gas in the natural environment.

Farmers can do this by planting native trees on farms, or others like pines.

Acland was involved in the partnership work and says it's been a frustrating experience.

"Well, fundamentally, it's really frustrating... We want this to be an enduring system that we have all worked on, which is what the original document was."

Acland is concerned about the pressure this will put on farmers, adding that many are struggling with mental health and staying optimistic about the challenges they face is getting harder.

Earlier this year, Minister of Agriculture, Damien O'Connor said the move will be good for farmers, helping them improve their productivity and profitability, while also reaching emissions targets.

Now we know what the situation looks like, let's have a look into the farming industry and what exactly is the issue?

Farming in numbers: What does the research show?

According to the Ministry for the Environment, agriculture is Aotearoa's biggest emitter of greenhouse gases, contributing to 50% of gross emissions in 2020, with the energy sector close behind at 40%.

New Zealand contributes to 0.17% of emissions globally, overall a relatively small percentage, according to a snapshot from the Ministry for the Environment.

However, that's not the main issue worrying government.

We have very high emissions per capita, among the highest across Annex 1 (a group that uses the same methods of reporting), and we are trying to lower that number to reach emissions targets.

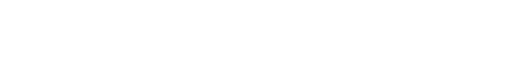

According to Stats NZ, NZ livestock numbers have changed dramatically over the last 40 years. Back in 1982, New Zealand had over 70 million sheep, but by 2019 this had dropped by over 60% to just 26 million. In contrast, as farmers cashed in on the dairy boom over the last decade or so, dairy cow numbers have increased by 82% to 6.3 million.

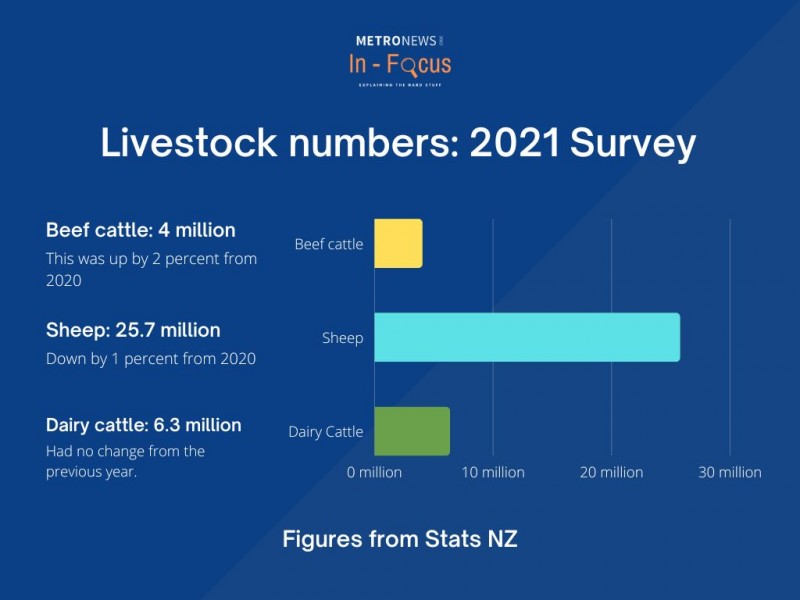

The big cause of concern for environmentalists is methane emissions.

According to the United Nations Environment Programme, 'methane has accounted for roughly 30 per cent of global warming since pre-industrial times' and is increasing faster than at any other time since records began in the 1980s.

Methane is a greenhouse gas, primarily emitted from livestock, and despite its short life in the atmosphere, research says it's 80 times more effective at heating the world than carbon dioxide over the first 20 years, according to the Environmental Defence Fund.

This is what has experts concerned about its role in warming, and there are urgent calls for reducing the levels.

Economic concerns:

Many are just opposed to the government proposal, but Steven Cranston is also against the He Waka Eke Noa one.

Cranston believes there will be no way for farmers to reduce emissions without reducing production, which will have an impact on the whole sector financially.

"I will point out there's nothing wrong with continuing to improve efficiency gains, and always striving to be better and more efficient, and I'm a big supporter of that, and we have been doing that very well for years in this country. And you know, we should do that more. But this idea that we're gonna get some sort of magical technology that's going to be available soon, that's going to allow farmers to dramatically reduce emissions, it's all smoke and mirrors."

However, Greenpeace's Lead Climate Campaigner, Christine Rose, doesn't believe either proposal is adequate, and an even bigger focus is required on intensive dairy farming, and too much power has been handed to the industry.

"The government has handed to the most polluting sector, the power to write up their own emissions management proposal, which we saw in He Waka Eke Noa. It's really unacceptable for the government to hand over that power to the industry, which is doing the polluting itself. And that can only lead to self-interested, suboptimal outcomes."

However, David Acland says it worked well to collaborate on a plan that worked for everyone, to 'create an enduring document'.

Rose believes claims the tax will have a large negative impact on the sector are 'hyperbole', and this is the least of measures the government should be taking.

She also suggests targeting and taxing fertiliser companies, saying there are not many, compared to the much larger task of regulating farmers all over the country.

However cutting stock numbers seems to be the biggest concern for farmers, worried about financial losses that come from reducing output.

Principal Economist at the New Zealand Institute of Economic Research (NZIER), Dr Bill Kaye-Blake believes it isn't as straightforward as it may seem.

"If you say that farmers have to get rid of 20% of their stock in order to meet their greenhouse gas targets, that means that they lose 20% of their revenue, and they lose a lot of their profit... however 20% would be worst case scenario."

Dr Kaye-Blake says the impact on revenue wouldn't be as big as logic might suggest, and the sector is very adaptable.

He used the agricultural reforms of the 1980s as an example and says predictions at the time foretold huge losses, however, they ended up a lot smaller than they thought.

"People adapt, farmers learn. And there are processes and technologies that exist, that they can adapt, they will develop new ways of farming. So the figures that they're throwing around now about 20% losses and so on, they are absolutely worst case scenario, and most likely won't occur."

Kaye-Blake believes overall the plan should have a positive impact, and the losses New Zealand farmers experience in the short term will be outweighed by preventing potential damages to the climate in the long term.

"This plan should be a net positive. The damages that we're avoiding are greater than the economic cost to us. We're giving up a little bit of economic value, but what we're getting back in terms of a healthy environment is absolutely worth it. So that's the key thing to understand about this policy. It's worth doing in terms of an economic-environmental trade-off."

There are also concerns raised about how it will affect the national economy, with dairy contributing a significant amount of our exports, as well as our GDP.

According to The Treasury, dairy exports contributed $18.6 billion to the economy in 2021, representing 23% of total export values.

However, Kaye-Blake says losses in the industry won't affect our economy hugely.

"Farming is about 6% of the economy. And if you add the processing into that, so milk, powder processing, processing and meat and so on, it rises to about 11 or 12% of the economy. So it is you know, it is important. But there's still around 90% of the economy that's not tied in with this issue."

"If we can learn to get more revenue from every animal, then we absolutely can keep our exports high, and keep our economy ticking over while producing lower emissions per dollar that we earn."

Emissions leakage:

Another concern raised by Cranston is emissions leakage.

This is a situation where as a result of one country tightening their emissions policies, another will 'pick up the slack', and the global emissions would remain the same, if not worse.

He predicts New Zealand farmers will be expected to meet tough emission standards at home and as a result will lose out to food producers in other countries, where the rules are not as strict.

Rose doesn't believe this is an adequate defence to not place these measures on farming and says it ignores the work of other countries around the world, and research suggests there is little risk of this happening.

The Climate Change Commission released a report, summing it up like this.

"While there will always be a risk of emissions leakage when countries unilaterally price emissions, the ample body of theoretical literature suggests that there is no consensus about the size of emissions leakage or where emissions would increase or decrease due to uneven implementation of greenhouse gas emissions reduction policies."

The report says there is no evidence of leakage from agriculture because emissions from farming have never been priced anywhere else in the world.

Let's wrap this up:

It's clear this issue has caused people, regardless of what side, to speak up and have their voices heard.

Farmers are concerned about their livelihood, how the plan will impact their business and their families. While not denying climate change, they don't believe this is the best way to make agriculture more sustainable.

They'd like more clarity on how money from the taxes will specifically be used.

However climate awareness groups like Greenpeace believe there should be even more further measures taken, and the proposed plan doesn't do enough.

Economic expert Dr Bill Kaye-Blake says he doesn't expect the plan to have as big an impact on farming profits as some might expect and says the sector is more adaptable than people expect.

Canterbury President of Federated Farmers David Acland hopes the submission process will have a positive outcome for farming communities, and an enduring plan can come from it.

The consultation phase closes 18th of November, and the plan will go to Ministers for approval early next year.

Share