In-Focus: Euthanasia

Azriel Taylor

Azriel Taylor

Share

In 2019, assisted dying was made legal in New Zealand, creating a large swell of support as well as opposition. Three years later, what is the state of opinion on the matter?

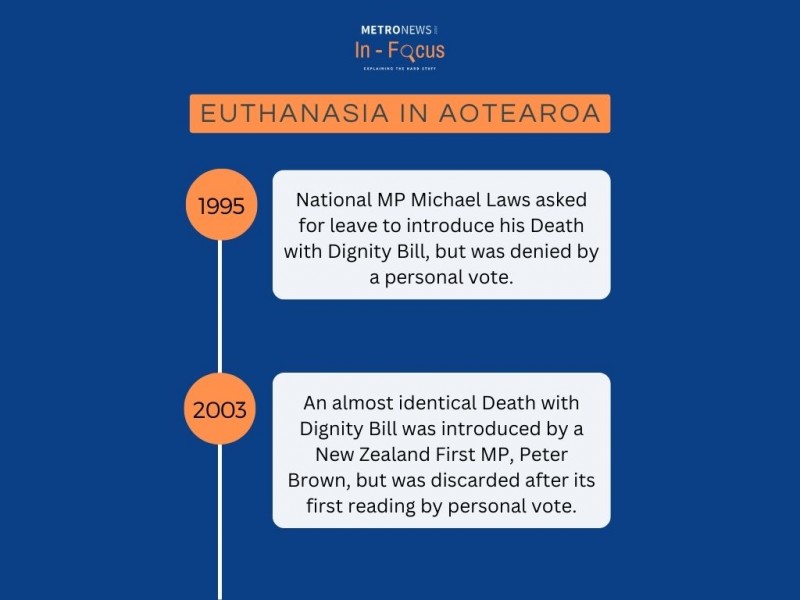

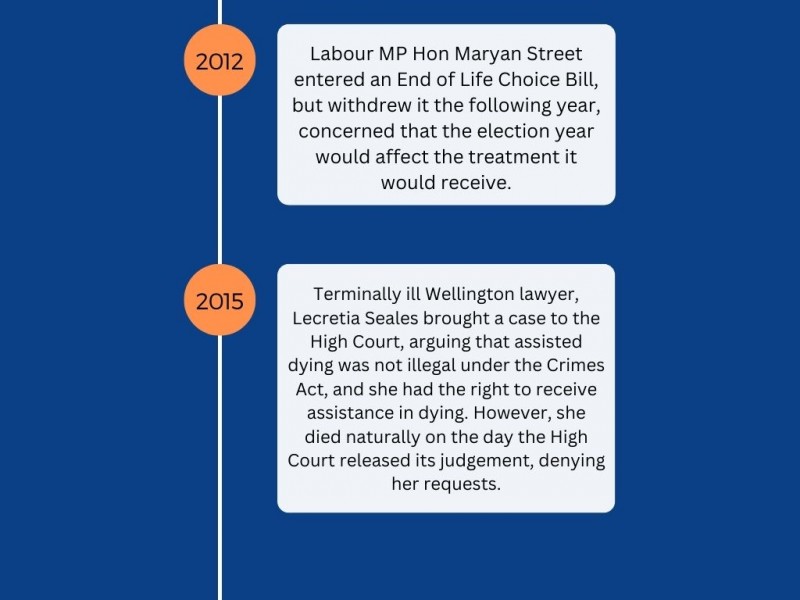

ACT leader, David Seymour's bill, was ultimately successful, but prior to him former Labour MP, Maryan Street tried unsuccessfully. However her bill later became the basis of the law as we know it now.

“I did hundreds of public meetings about this. And anyway, 2014 came, and I was booted out of Parliament. My bill disappeared from the ballot, or the ballot is emptied out at election time, and it's a whole new parliament. So, people have to reintroduce the bill, David Seymour decided to pick up my bill.”

The push for assisted dying wasn’t just within the walls of Parliament, and people like the late Lecretia Seales tried within the courts to fight for the right to die with dignity following her terminal cancer diagnosis.

Yet the reaction to the act being passed wasn’t all positive, with groups like Euthanasia-Free NZ, Doctors Say No, and healthcare organisations such as Hospice NZ and the World Medical Association condemning it, holding the belief it wasn’t ethical.

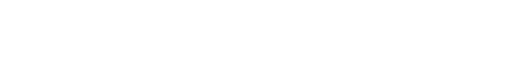

But first, let’s get some background on the topic, how has it evolved over the years?

A short history of euthanasia in New Zealand:

One of the most recent and high-profile advocates for euthanasia was Lecretia Seales who was diagnosed with an untreatable brain tumour in 2011. Four years later she took a case to the High Court claiming her doctor should be able to help end her life without facing a murder or manslaughter charge under the Crimes Act.

She argued that under the Bill of Rights Act 1990, she had the right to not be "subjected to cruel, degrading, or disproportionately severe treatment".

However, Te Ara's records show she died naturally the same day the court released its judgement saying she had lost her case.

Although, the fight didn't end after her passing.

Lecretia was voted as New Zealander of the Year in 2015 by the New Zealand Herald, and her family fought to continue her legacy.

Her husband, Matt Vickers, thanked everyone for voting for his late wife in a video and urged others to make submissions to the Health Select Committee to make assisted dying legal.

“On behalf of Lecretia, I’m asking you – begging you, actually – to write a submission in support of change – for my sake, for Lecretia’s sake, and more than that, for your own sake and the sake of your loved ones.”

This case was important in the course of New Zealand's history, as it challenged the law regarding the rights of Kiwis to not suffer, and highlighted a need for clarity on the topic.

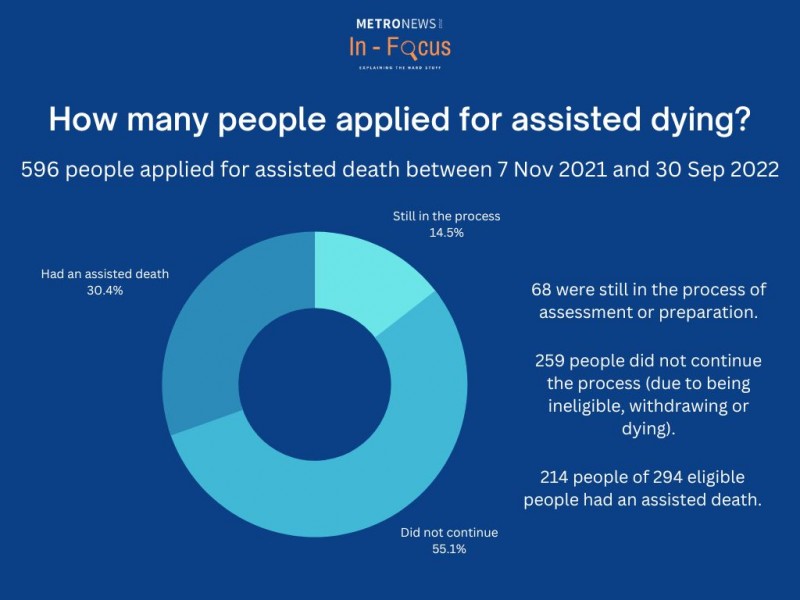

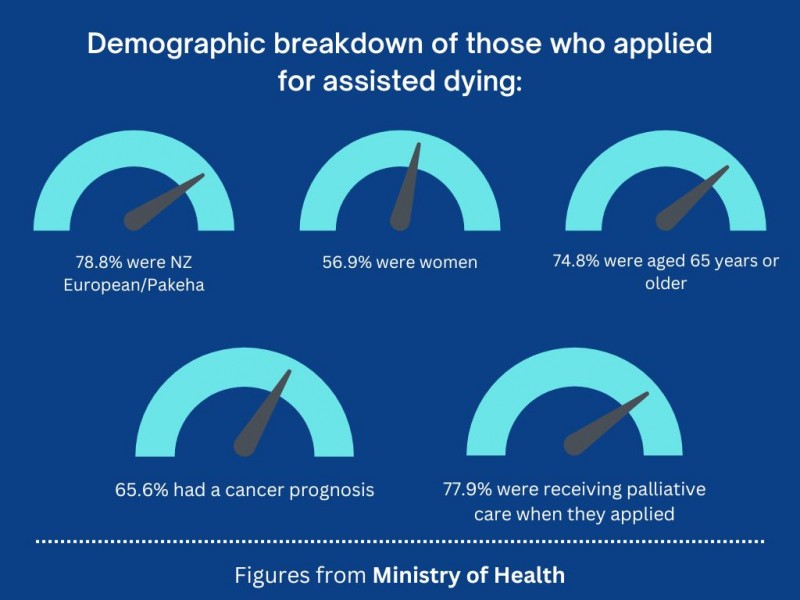

Euthanasia in numbers, in New Zealand:

These are the latest figures reported on the Ministry of Health website, giving an in-depth look into how many people have used this service, since it became legal.

The state of public opinion:

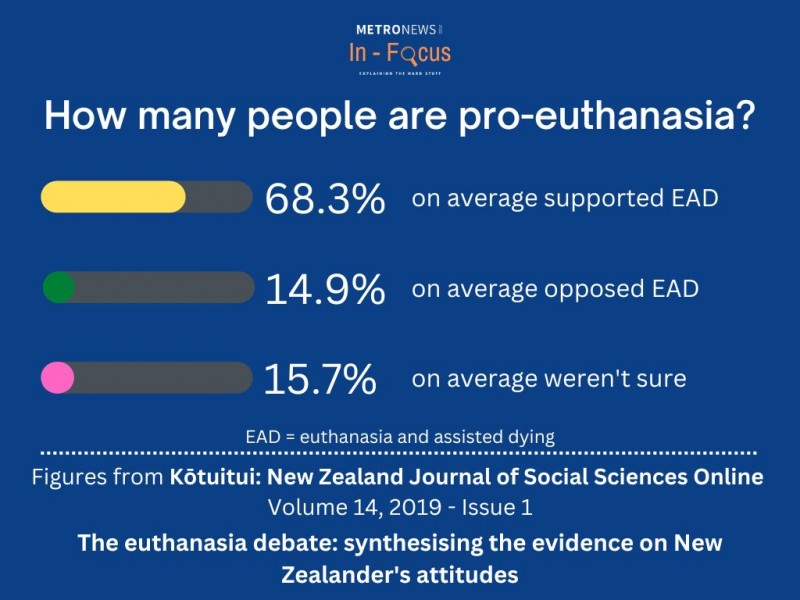

These are the average figures collected from nearly all surveys and studies done in recent years that investigated public opinion on assisted dying, with 36,304 people surveyed across all of them.

This shows a majority of Kiwis supported assisted dying. Surprisingly, these figures show there were more people that were unsure, than those who purely opposed it.

However, it may not be as clean-cut as these percentages show.

A poll was completed by Curia Market Research in November 2019, asking 700 Kiwis what they thought the End of Life Choice Act was going to do.

What this revealed was confusion about what it actually involved.

For example, 74% of respondents thought the End of Life Choice Bill would legalise people choosing to have machines turned off that are keeping them alive.

In reality, this has been legal for years under the Bill of Rights Act 1990, section 11, which states that everyone has the right to refuse any medical treatment.

Along the same lines, 70% of respondents thought it would legalise choosing not to be resuscitated. However, by the same section of the Bill of Rights Act, it was already legal in New Zealand to have a do not resuscitate order.

Bring in the people:

Former Labour MP, Maryan Street, is someone well-versed in pioneering assisted dying rights in New Zealand.

She tried to make it legal in 2012, and it has been a seven-year battle to pass it into law.

The topic of dying is one she's very familiar with, having plenty of experience with people close to her suffering toward the end of their lives.

Her sister died at 54 years old from motor neurone disease, which makes processes like breathing, swallowing, speaking, and moving more difficult, eventually leading to death. Currently, it has no cure.

She was also by her mother's side as she died at home.

She said these experiences shaped her views on end-of-life suffering and she wants others to be able to die without being frightened and scared.

"If you would rather not get to that stage, and you'll have the fear and anxiety that brings about, you would want to be able to choose your moments, to go peacefully, with your loved ones around you, in a place of your choice, and a moment of your choice with a method of your choice."

She said her mother would most likely not have chosen to receive assisted dying due to her religious convictions as a Christian and wasn't sure if her sister would have requested the service. However, she said she wanted to give people the option, as it wasn't available when they passed.

"But having that choice, gives people who are living with a terminal diagnosis, the chance to live what's left of their life, rather than having that time eaten up with the fear of dying, the fear of how they're going to die, and that is really liberating."

She put her End of Life Choice law as a members bill in 2012, however it was never drawn from the ballot and she withdrew it later.

But that didn't spell the end for her efforts, as the Leader of the ACT Party, David Seymour, decided to take her bill and work with her to get it into law, altering two main things about it.

He reduced the expected time of death (prognosis) from 12 months to six months, and took out her Advanced Directive provisions, which would have allowed people with dementia to sign a statement, "setting out in advance the treatment wanted or not wanted in the event of becoming unwell in the future".

This was a big part of her bill, as from her experience speaking with elderly people while preparing her bill, she found that many were afraid of dementia, and not able to choose.

However, they continued to work together on it, and eventually, it was drawn from the ballot and put into law.

Earlier this year, she experienced what it was like to support someone through the process, as one of her friends had a brain tumour, and wanted to exercise his right to die with dignity.

"It was extremely peaceful. It was his choice, and the process worked to preserve his dignity in the face of an inevitable and distressing end. And so I was really pleased for him. The law is working the way it was meant to work."

Jake, a Christchurch resident, who had to care for his father toward the end of his life, wishes his father had the option to have an assisted death.

His Dad lived in another country, and when he got the call that he was sick, had no hesitation in going to see him.

Over the course of months, he watched his father continually get worse, suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, leading to him requiring oxygen tanks to breathe, and eventually moving into full-time care at the hospital. Although it's not a terminal illness, it can be fatal in bad cases and lead to an irreversible decline in physical state.

One day he received a call, and a nurse told him that his father had fallen and wasn't connected to an oxygen tank.

That was when Jake had a choice to make, as the nurse asked him if he wanted them to revive his Dad.

Despite his father having a "do not resuscitate" order, as power of attorney, it was Jake's decision to make.

"Well, I said just do your f***ing job, you just try to save him. And they couldn't do it."

After trying to save him, the hospital staff informed him that his Dad had passed, after a gag reflex during a procedure filled his lungs with vomit.

He now believes euthanasia would have been a better option.

"Had we known how it was going to be? I think we would have or he would have definitely opted for that option. Assisted suicide, done in a safe way."

This experience gave him sympathy for those who wish to end their suffering, giving him a sobering perspective on death.

"I mean, it really is your last option, because there's no avoiding the fact that a person is going to die within a short amount of time, and it has the potential for them to not pass away in the most pleasant of ways, I mean, you don't know how it's gonna happen. If a person is in absolute agony 24/7 and even the strongest painkillers aren't scratching the itch, I would say that's a pretty good case for euthanasia."

However, some medical professionals in the country have objected to the law, including Hospice NZ.

In a statement online updated last year, they said assisted dying has no place in palliative care, and major improvements in healthcare should happen first.

While respecting and acknowledging varying perspectives, from a variety of backgrounds, they believe it should be a priority for the Government to improve access to quality palliative and hospice services first.

"Only when all New Zealanders have equitable access to good quality end-of-life care can a balanced discussion begin," they said in their statement.

Grant Gillet, a Professor of Medical Ethics at the Bioethics Centre of the Otago University Medical School prepared a report for the New Zealand Medical Association, speaking against assisted dying.

Gillet cited a section of the Hippocratic oath, "I will not give a fatal draught to anyone if I am asked, nor will I suggest such a thing".

This oath is taken by physicians, swearing to stand by certain principles of medical ethics, and it dates back to early Greek medicinal practice.

Gillet said the principle acknowledges the "intrinsic value in human life", and it is partly because "nobody quite knows what the future will bring, even in the last days of an illness".

In the report, Gillet quoted The World Medical Association's statement on Physician-Assisted Suicide.

"Physician-assisted suicide, like euthanasia, is unethical and must be condemned by the medical profession. Where the assistance of the physician is intentionally and deliberately directed at enabling an individual to end his or her own life, the physician acts unethically. However, the right to decline medical treatment is a basic right of the patient and the physician does not act unethically even if respecting such a wish results in the death of the patient."

One of the bigger groups against assisted dying in New Zealand is Euthanasia-Free NZ, and the Executive Officer, Renee Joubert, would like some more safeguards introduced into the law, rather than trying to repeal it.

"We don't think it's realistic to try to get the law repealed. It's never happened overseas."

Some of the requirements she would like added to the law, are:

- A mental competency test when receiving the medication.

- Compulsory discussion with a palliative care specialist.

- A mandatory waiting period between the first request, and the administering of the medication.

However, Street believes there are enough safeguards to make sure someone is mentally competent enough to make a decision, as outlined in section 5 that the person requesting the service has to be competent to make an informed decision. Also if two medical practitioners aren't sure a patient is competent to make the decision, a psychiatrist is called on to make an assessment, as outlined in section 15.

Although it isn't compulsory for someone to speak with a palliative care specialist, it is the responsibility of the attending medical practitioner to discuss their end-of-life support options, including palliative care.

As for the third concern, it isn't exactly clear if there is a compulsory waiting period.

Street said within the law, there is a seven-day waiting period between the request and the administering of the medication, however, some groups against assisted dying laws claim that it would be possible for someone to receive the medication just four days after the request was made.

Let's wrap this up

Assisted dying has had a long history in Aotearoa, with many trying to make changes to allow for people to 'die with dignity' such as Lecretia Seales and Maryan Street.

Although statistics show a majority of Kiwis supported the law, other research shows many people were unclear on what it would do.

Groups and organisations such as Doctors Say No, Hospice NZ, and Euthanasia-Free NZ, still have ethical concerns and want more safeguards introduced.

Do you need help?

If you need help after reading this, please find below a number of resources and organisations to reach out to for help.

Information regarding assisted dying services

Call 0800 LIFELINE (0800 543 354)

or send a text to HELP (4357)

Free call or text 1737 anytime for free counselling services

Share