They hired out a youth centre in Christchurch and employed 25 friends to meet growing demand. But the orders were coming in faster than they were able to send them out.

“We were selling product that we didn’t have in our hands. We had to fly the product from Sweden, put the foam in them and mail them out.

“We were sitting in the back of Merivale McDonalds printing out our orders because the internet was better. We were there at midnight, printing, and we had this realisation we couldn’t print the labels faster than the orders were coming in.

“It hit this crux point that we sold 13,000 mats. We realised we weren’t going to get these orders out by Christmas, and it was the first real crushing moment for me.”

But at the final buzzer, a shipment of Shakti mats arrived. A Christmas miracle.

“We turned it around with 25 people in an hour and a half. Got out 99 percent of them before Christmas. It was this huge victory. It cost me like two years of my life.

“It was surreal. Just a surreal moment.”

Heslop and the Shakti team moved their headquarters to Europe, first Portugal and then the Netherlands. There is still a warehouse in Amsterdam in charge of European product. It’s also expanded to have distribution centres in the United Kingdom, while the New Zealand headquarters is based in a warehouse in Christchurch.

Heslop has learnt a lot. He jokes about his limitations in business.

“I’ve learnt that I’m better at starting a company than running it.”

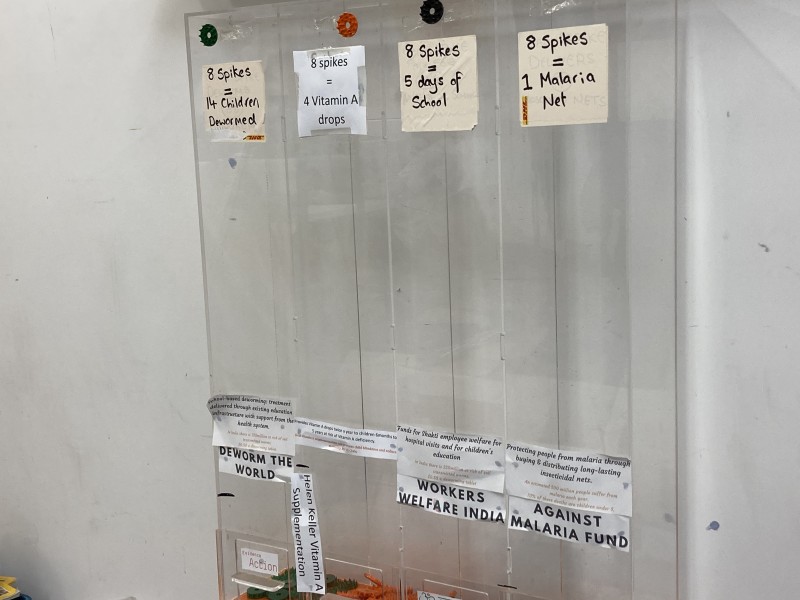

Charity is important to Heslop, and he has spent a lot of time finding the ones with the most beneficial outcomes. His team in Christchurch are given tokens, where every day they can decide a charity to invest in using some of the Shakti mat proceeds - vitamin A tablets, deworming pills, education for the children of employees in India.

Business decisions were easy to make back when Shakti had two employees who were fine to work out of fast-food outlets. Now Heslop is responsible for workers all around the world who depend on him.

“I believe companies have an obligation to the stareholders in the company. Customers, employees. It involves the environment and the rights of society. It’s way harder to balance. It’s easy if you think of a company as a machine designed to make profit. But if a company has 10, 15, a hundred objectives to meet it becomes a much more human endeavour.”

Heslop juggles the human side of Shakti with the business side. He feels the weight of people depending on him.

“You grow up so flipping fast when your decisions have material consequences to real people. You’re banging your head against a wall, you don’t know if you can take it anymore, but you get through it. You have to.”

Maybe he does know something others don’t. Maybe all the late nights and early mornings, the nights spent in a tent, the failures, and the successes of his business have given him an insight that most won’t reach. Heslop’s world might be shrinking, but he’s growing into his responsibilities, one day at a time.