He's a busy man, John Minto, but kind and generous with his time. So much so, he took time for me. Here's his story.

He was on a National tour to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the 1981 Springbok tour when we caught up. Over the phone, we spoke about his life, career in activism, politics and education.

Minto was born in Dunedin. The second child in a big Catholic family. He learned to value social justice at a young age.

His start in activism came in 1975. It was through Halt All Racist Tours, known as HART. HART was opposed to letting the Springboks rugby team tour New Zealand due to South Africa's racist policy of Apartheid. Minto became the national organiser of HART in 1980.

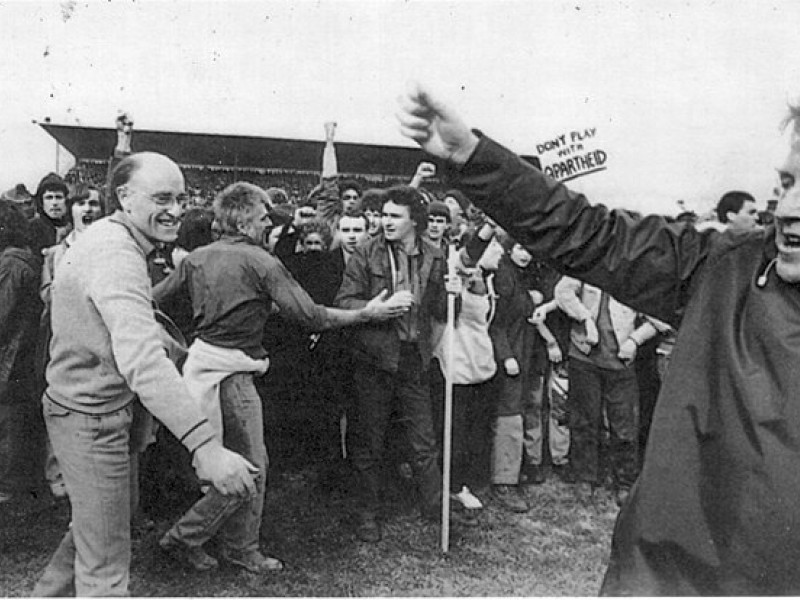

Despite the opposition, Prime Minister Robert Muldoon invited the Springboks to tour in 1981, and it led to fierce protests which divided the nation. Minto says Muldoon’s decision was an example of cynical politics, as he knew the tour would go down well with key battleground political seats. The police employed violent tactics to control protesters. Minto was in the thick of it.

Over the course of the few months that the team toured, Minto says the police turned from an ordinary force into a paramilitary one, equipped with riot gear and batons which were nicknamed ‘Minto bars’.

“If people are breaking the law and stopping the games, you deserve to get arrested, but you don’t deserve to get your head bashed in, and that happened too often”, Minto says.

He agreed with an assessment made by a policeman that it was “sheer luck” no one was killed during the protests. Minto says people were getting angrier and more frustrated by the day. He thinks if the tour had gone on another week people could have been killed.

One of the key moments of the protests was the cancellation of a game in Hamilton, when activists flooded the field. They’d scoped out the area weeks before and planned the best way to get in. Minto doesn’t think the police believed the protestors would even try to get onto the pitch, but they did, and the effects were felt all around the world.