Watching, ever watching, Te Ahu Pātiki stands fast. As cloud swirls, glimpses of water are caught in the bay far below. Spirals of smoke drift up into the sky, from the place where land meets sea. Down the road winds and spills, down into fertile valleys and around the waters edge. Onward, ever narrower until it reaches the place over which the mountain of Te Ahu Pātiki watches: Koukourārata.

Salt water laps the shore. Birds sing in forest pockets above. Homes hug the edge of the bay, gathered in a place where beauty dwells. For those who are listening, two rivers flow free, dancing down their hillside paths, clothed in a mantle of bush once more.

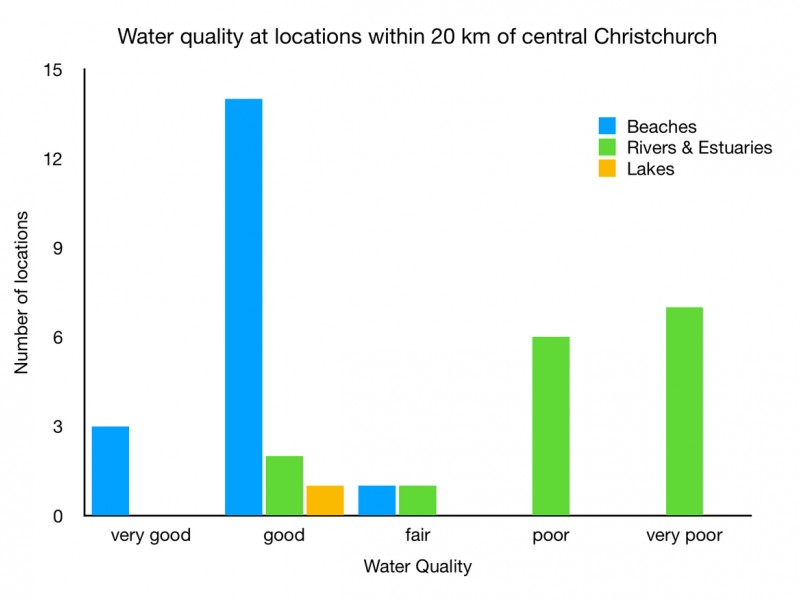

In a time when headlines are rampant with river water issues and the majority of Canterbury water quality is declining, the Māori community of Koukourārata are paddling a different waka. Instead of eroding river banks and stagnant water, their rivers are a place of beauty and life, beginning to flow as they did hundreds of years ago. They’re digging into their whakapapa, their roots of whanaungatanga, manaakitanga and kaitiakitanga. But it hasn’t always been this way.